Editor's Note - Surfing The Channels

I’ve realized over the years that it is increasingly difficult to keep up with advances in the fiel...

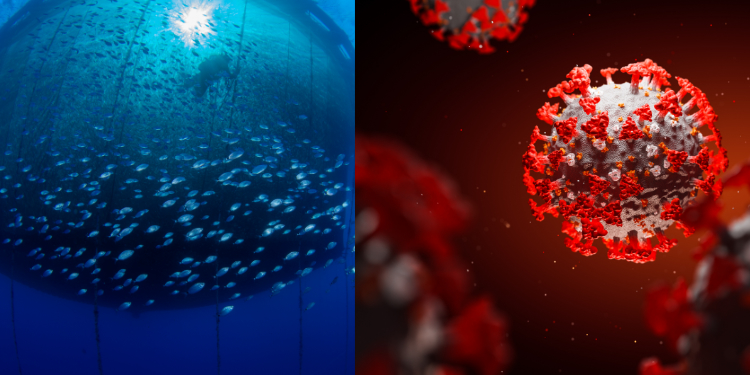

It is now just about one year since the first stay-at-home orders were issued as the global COVID-19 pandemic began to rage. There are now signs of hope that the worst of the pandemic may be over and that green shoots of recovery are at hand, despite severe covid fatigue leading many to abandon the social distancing and mask wearing that got us here, and the rise of new more transmissible virus variants. By a miracle of modern science, suitable vaccines have been developed in record time and distribution is now underway. In the year that has passed, investigators have conducted surveys and other evaluations to gauge the impacts on aquaculture.

First, it is worth repeating that aquatic foods are the main source of nutrition and livelihoods for around 800 million people and that nearly 3.3 billion people obtain 20 percent of their per capita intake of animal protein from aquatic foods. Importantly, in the context of covid, aquatic foods are among the most-traded food commodities and the seafood sector as a whole is truly globalized. In 2018, about 38 percent of total fish production, worth more than $162 billion, was exported. Together, salmon and shrimp account for 35 percent of the total value of traded seafood.

It is in this context that the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on aquaculture can be evaluated. Like nearly all sectors of the global economy, aquaculture has faced severe disruptions in all phases of the value chain, with shocks in one stage rippling to other stages. Despite most countries designating aquaculture as an essential activity, and thus exempt from the most draconian lockdown measures, the FAO is projecting a slight decline of 1.3 percent in global aquaculture production, after decades of positive growth. The FAO also projects that the Fish Price Index in 2020 for most traded species will also fall.

The main challenge for aquaculture producers around the world has been the loss of normal domestic and export market channels as consumer demand for what is a highly perishable item was severely curtailed by stay-at-home orders. In the United States, around 70 percent of seafood is consumed in restaurants and thus food service demand for seafood evaporated. Retail prices declined and were more volatile. Globally, many fish markets, normally very crowded places, were closed by social distancing requirements. Global trade was further disrupted by border restrictions and reduced access to air freight and transportation logistics generally.

One of the potentially positive outcomes of the pandemic has been the transformation of the retail seafood market associated with increased retail demand. Consumers can now order seafood direct from producers online and receive home delivery. In many places, supply chains have been shortened, emphasizing consumption of locally sourced fish. Consumers are also purchasing more shelf-stable and value-added convenience seafood. It seems likely that this e-commerce trend will continue after the worst of the pandemic has passed.

Although the loss of traditional markets has been the greatest challenge to most aquaculture producers, they have faced other challenges as well. The lockdowns have meant that farm labor, including skilled technicians, were not available to conduct normal farm or hatchery operations. Transportation and logistics for obtaining seed and feed left producers scrambling. In particular, the inability of processing plants to receive harvested raw material due to a shortage of labor meant that market-ready inventory accumulated on farms as harvests were delayed, increasing costs and the likelihood of losses from diseases. This disrupted cash flow, weakening the finances of aquaculture businesses.

The COVID-19 pandemic has represented an acute shock to aquaculture systems worldwide. The intensity and scale of impacts need to be seen in the context of more chronic anthropogenic stressors associated with climate change like eutrophication, harmful algae blooms, heat waves, hypoxia, flooding and severe storms. The disruptions of covid are magnified by these stressors, causing additional economic losses to the most vulnerable producers. Clearly a more holistic response that includes consideration of these stressors is needed.

Responses to the COVID-19 pandemic have emphasized the idea of building resilience to future shocks, rather than simply coping with the crisis at hand. Although rapidly deployed relief and support programs have been essential as safety nets in the short term, Eddie Allison of WorldFish talks about a more long-term approach to “build forward better,” rather than simply restore business as usual. To do that, strategies and actions that focus on building long-term resilience are needed, especially for the most vulnerable. Certainly there are exemplary cases of coping and recovery strategies that could be emulated more widely.

Much has been made about developing resilience capacity in the wake of the covid pandemic. Resilience is one of those development buzzwords for which definitions vary but is often considered to be synonymous with adaptation and reduced vulnerability. In ecology, resilience is the capacity of ecosystems to withstand disturbance and return to a previous stable state. The Stockholm Resilience Center defines resilience as “the capacity to deal with change and continue to develop.”

One key aspect of resilience is learning from past experience. Exposure to a hazard such as covid, in an ideal world, would motivate people to take action to reduce the effect of future shocks. Perhaps its my own covid fatigue, but I’m skeptical that we will learn from this dark episode and dedicate time and resources to build resilience into aquaculture systems. Perhaps it is human nature to respond only to the crisis of the moment and not prepare for the murky black swan of the future.

Perhaps it is more realistic to think about resilience in terms of flexibility and having options. One of the lessons learned from the pandemic is that aquaculture sectors should broaden the diversity of marketing and supply chain options. Operations that are nimble, flexible and embrace change should be more resilient to future shocks.

— John A. Hargreaves, Editor-in-Chief